Come morning, I sleep in until I can’t possibly anymore. Claw my pillow until every inch of tiredness has been attended to. Then brushing teeth in the damp, green cupboard of a communal bathroom, sitting on a top-loading washing machine that abuts the shower. Then breakfast.

I’m surprised that there’s any left. It’s almost 10h00, and there are piles of eggs and bread still on the counter for toasting. And coffee.

Oh god. coffee.

Proper coffee made from instant powder and milk, not heaps of grinds boiled in water to make a terrible, gritty approximation. I find a large mug and start making some with relish. My standards have dropped, but it makes me so much more easily satisfied. It’s hard to slurp hot coffee through a grin.

There are transiting travelers everywhere. A Dutch student typing up a thesis or research project of some sort on free trade. Some Germans on a class trip of some kind – anthropology perhaps? The lecturer seems disappointed that some pygmies they had visited were not authentic.

“But weren’t they naked?” the guest house manager asks helpfully.

“Yes, but they were only naked for us. They aren’t naked normally”

“Maybe there are real naked ones further out?”

The lecturer says something disappointedly as he walks out of earshot. I think it’s something about not being sure that there are any genuine pygmies left in that area.

Oh Africa.

I’m sure there is a wider context to this exchange, but this fragment is more than entertaining enough. Some European lecturer’s African fantasy caught in mid air, transcribed, and danced into a blog – months later – by a stranger’s fingers.

I caught you, sir.

I sit down to charge my laptop. Draft a blog post recalling our evenings in the back garden of the house in Gulu. It’s much easier to write now, further away from the place and better able to sift through the memories. Start seeing the connections at last.

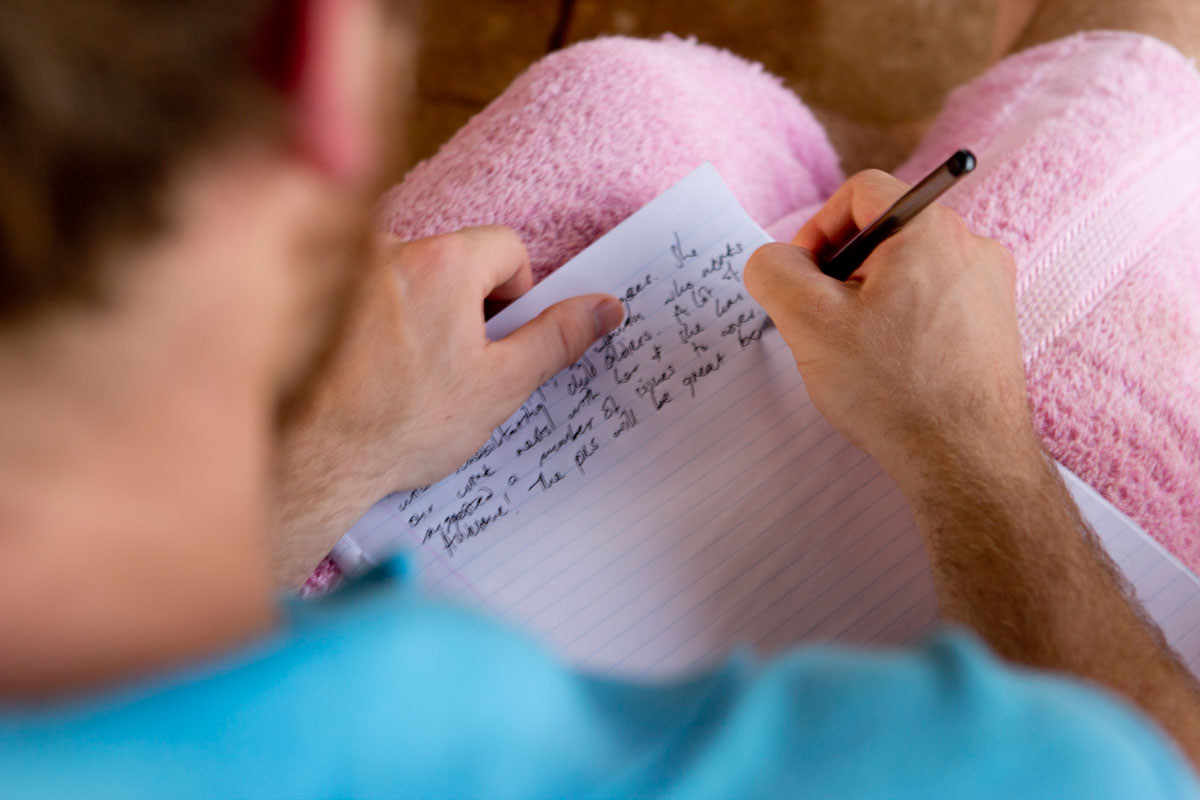

I find Saskia up on the roof, quietly writing in her journal. Probably catching up on last night. Lamenting the first half of her bus trip, spent next to an uncomfortably loud man soaked in gin. For reasons I cannot understand, neat gin in sachets is the clear spirit of choice in Uganda. I can’t see the appeal, but the reek of gin is an unmistakable warning hanging about overly social individuals.

As the sun disappears, Saskia and I update journals until it becomes too dark to continue. Then we just sit in the fast-approaching dark chatting. She is wondering about home. About her boyfriend, Gareth, and being able to bring him to understand this place. It’s tough, being here and thinking about home.

The context shift is just so large. Expecting someone who wasn’t here and didn’t breathe the burning garbage in the evenings and didn’t ride on the chicken buses to understand is perhaps asking too much. But if it’s unreasonable to expect partners to know what this place means to us, it’s not unreasonable to ask them to understand that we are changed. That we are richer people for having come here. And that we need the space and understanding to process things when we return. The right to be frustrated at never really being able to explain what Gulu and Kitgum were.

Saskia sounds uncertain that Gareth will understand, and I can’t really give any reassuring advice. When you travel, you change. That’s unavoidable.

And the deeper you go, the more to the edge of the world you push yourself, the more profound that alteration becomes. How a changed you brushes up against the rest of the world when you return is never guaranteed. You work it out a day at a time, I guess. Or else you run away again, as soon as you can, to the places with different light, different wind.

The smell of rubbish burning in the evenings.